Radical Candor Is Not An Excuse For Bad Feedback

I’ve seen a few articles recently about a concept called “radical candor.” It is what you would expect it to be – the concept of pointing out the “elephant in the room” problems in organizations. It’s considered to be blunt, honest feedback. Some people are likening it to “fierce conversations,” “frontstabbing,” or “mokita.”

I’m not sure what to make of this. On one hand, it’s great that a conversation is emerging about how to address those “emperor has no clothes” moments. But I’m concerned about the label it’s getting. Frontstabbing?! Really?!

For organizations to be successful, they need to find ways to address touchy subjects. I’m not saying it’s easy. And it does take honest conversation. But when the honest conversation is labeled radical candor, that almost gives legitimacy to being insensitive. (As in, “Let me share with you some radical candor …”)

Every organization has elephants. Every. Single. One. You can call them your traditions, legacies, or whatever. But every company has some sacred cows or things they just don’t talk about as a group. They might talk about them behind closed doors or with body language, but they don’t get addressed. And they should. It reminds me of “The Abilene Paradox.”

No one wants to be the person who points out the obvious. Let’s face it – the person who usually points out the elephant is often an external consultant, a new employee, or an exiting employee. Someone who doesn’t realize they’ve just stepped in it or has no fear of retribution. Organizations need to create feedback mechanisms that do not create an atmosphere of fear when it comes to feedback.

Blunt, honest feedback does not have to be synonymous with mean-spirited. I’m sure I will get some pushback on this but I believe we’re sending the wrong message to tell people authentic feedback is the same as being “fierce” or “stabbing” or “radical.” The purpose of feedback is to create change. It should be delivered in a way that does exactly that. The sender needs to know their audience.

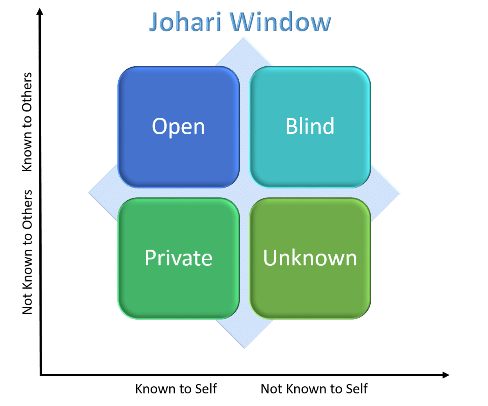

Instead of creating a new buzzword du jour, organizations need to create mechanisms for employees at every level to provide feedback. And they need to train employees on the best ways to deliver and accept feedback. It reminds me of the Johari Window, which was a communication model created by two American Psychologists, Joseph Luft and Harrington Ingham. The window has four panes:

Open: These are traits that both the participant and others are aware of.

Private: These traits are known by the participant only. A participant can move these to the Open pane through the process of disclosure.

Blind: These traits are only known by others. Others can move these to the Open pane through the process of feedback.

Unknown: These traits are not known by the participant or others. Maybe because they don’t apply in the relationship or they haven’t been witnessed.

The focus of the Johari Window is to use feedback and disclosure as a way to build trust and relationships. When individuals have trust, they do not need to “frontstab” each other. Trust lets each person know the feedback is coming from a place of sincerity and is well-intended. That’s not to say the conversation won’t sting a little – sometimes feedback does. But the recipient knows the feedback was not meant to harm. Just to help.

Organizations need to teach employees how to give and receive good feedback. And create a culture that encourages it at every level of the organization.

Images courtesy of Sharlyn Lauby

2